Acton Answers: Why the Socratic Method?

OCTOBER 7, 2014

“You’re not a consultant. You own this business. What are you going to do?”

The Socratic Method is a highly effective tool used in the Acton classroom. Boring lecture halls, faces plastered to computer screens, professors rambling on, we’ve all been there.

While you might learn a few facts you can recite on request from classrooms like this, the reality is that you’re unlikely to learn anything that would change the way you see the world—or the way others see it.

At Acton, we prepare talented, disciplined students for extraordinary lives as principled entrepreneurs. This mission carries over into everything we do, including the design of our courses and how we teach them. We take our students’ aspirations seriously.

We recruit successful business leaders as teachers. They in turn use pedagogy that has proved effective in helping students acquire the tools, skills, and perspectives needed for success in business and balance in life.

If you’re skeptical — if business school seems like an unlikely place to learn the entrepreneurial mindset — we are with you. When it comes to forming business leaders, how you teach is even more important than what you teach.

Traditional lecture-style teaching casts students as passive responders. Driven by the grading system, students focus on meeting the teacher’s expectations. They learn to repeat ideas and apply tools in a prescribed way.

Entrepreneurship, on the other hand, requires initiative and engagement, the courage to improvise, a sense of empowerment, and a persistent, inspiring dream.

Lecture-style teaching doesn’t encourage these qualities in students. That is why Acton is committed to case discussion.

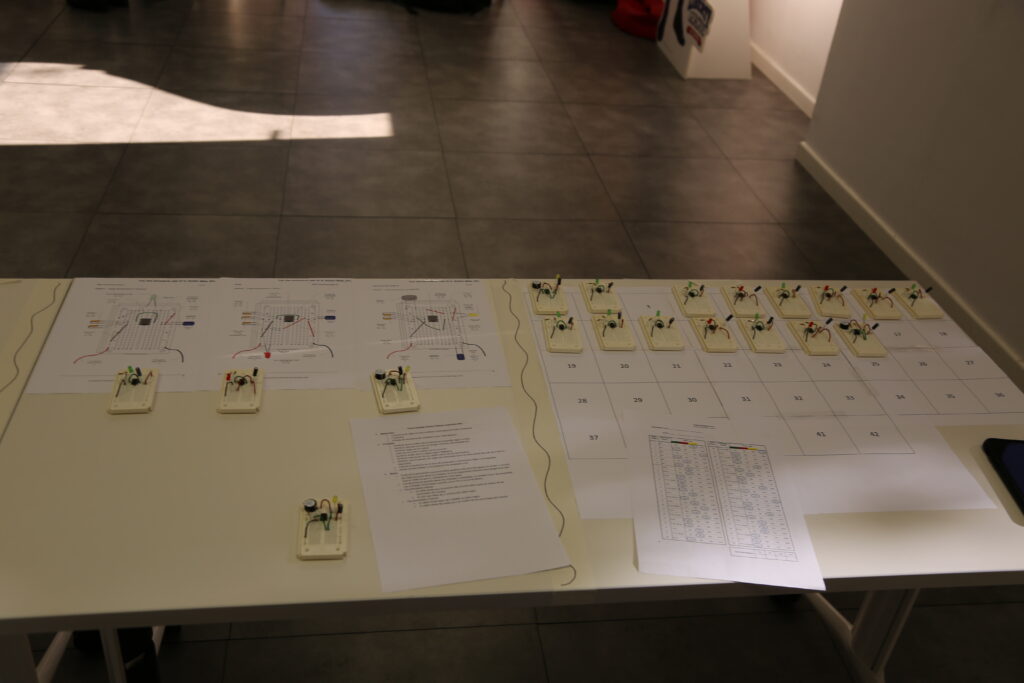

A good case discussion is the business equivalent of a flight simulator. Students step into the shoes of an entrepreneur facing a critical business decision. The teacher holds them accountable for the facts of the case, presses them to make commitments and take action, and keeps raising the stakes. As the conversation unfolds, students experience the consequences of their choices.

The class starts on time with an energetic sense of anticipation. The teacher quickly situates the day’s discussion in the flow of the course and restates lessons learned from the last discussion.The teacher “invites” a student to open the discussion and lays out a dramatic situation, an entrepreneur facing an agonizing dilemma, punctuated with an inescapable choice: “You must decide now. Will you sell your business for $500,000 or risk losing it all?”

A lively debate ensues.

Students address questions, comments, and challenges directly to one another. Students make their points concisely and build on other’s contributions. The teacher makes notes on the board to focus the argument as the fast-moving exchange progresses from questions about the ideal customer to an argument about the cost of serving that customer, from speculation about how soon competitors will enter to deal proposals designed to benefit all players. Students who present numerical analyses take time to first connect their numbers to the question on the table.

“You’re not a consultant, now. You own this business. What are you going to do?”

At one point the teacher calls “time out” and takes three minutes to review the formula for valuing an indebted company. When the teacher ends the “lecturette,” calls “time in,” and poses a new question, energy rebounds.

At moments you feel as if you’re watching a mind meld – the students connect so quickly, like parts of a single brain. An hour flies by. Finally, the teacher asks the students what they will take from the day’s discussion.

They identify specific lessons learned and link them to their own goals in business. Class ends, but students continue arguing. The discussion spills out of the classroom and into the hall as they share a sense of accomplishment at what they have learned together and what they have taught one another.

So, why does Acton teach this way?

Because case discussion is a proven way to teach business leadership.

Students preparing for and participating in case discussions learn more than just facts — more than just tools and analytics and how to apply them.

They learn to use facts and analysis to qualify their judgments. Judgment includes the ability to identify priorities, assess risks and rewards, and make the best guess in light of the data. During a case discussion, the teacher will press students to move from facts to analysis to judgment as they make critical business decisions.

Time pressures and an action-oriented atmosphere also force students to focus and choose carefully how to spend class time. They learn to make decisions under pressure. What is more, case discussion makes students practice the conversations required to make things happen.

Case discussion lets aspiring entrepreneurs “practice like they’ll play.”

It also gives students perspective through experience. In each class, students live with the consequences of their decisions — good and bad. It is a game, but when students identify with the entrepreneur-protagonist, the emotional experience is real.

As experience accumulates, students get better at recognizing patterns. Their reflexes improve.

In short, case discussion gives aspiring entrepreneurs the benefit of learning from hard knocks without incurring real world costs.

It’s easy to explain what the Socratic Method is, but it’s nearly impossible to visualize the unique experience without witnessing it firsthand. If you want to see the Socratic Method in action, our classroom is open. Sign up to visit a class or feel free to contact us directly with questions.